Penn’s “Sylvania”

Pennsylvania derives its name from William Penn’s land grant — “sylvania,” meaning forest. Before European settlement, the region was covered in dense temperate forests rich in biodiversity and stewarded by Indigenous peoples.

Beginning in the 17th century, widespread clearing for agriculture, settlement, and industry transformed the landscape. By the 19th century, Pennsylvania had become one of the leading timber-producing states in the nation. Prosperity came at ecological cost: soil erosion, watershed disruption, and biodiversity loss.

Conservation movements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries slowed some of the damage, establishing state and federal forestry systems. Yet today, new pressures — driven by climate change and atmospheric pollution — are reshaping Penn’s Sylvania once again.

A Troubling Canopy Shift

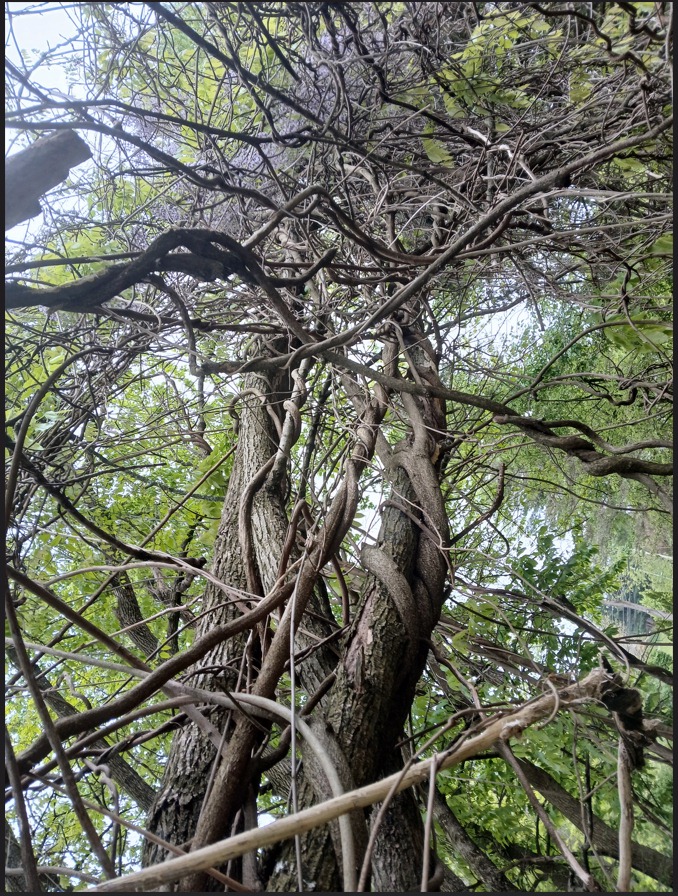

Across Pennsylvania, old-growth and mature trees face mounting stress from rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, invasive species, and atmospheric chemistry changes.

As canopies thin, opportunistic vines climb higher, overtopping weakened trees and accelerating decline. What appears at first glance to be simple overgrowth reflects a deeper systemic imbalance.

Forest decline disrupts biodiversity, destabilizes soils, alters hydrology, and reduces carbon sequestration capacity. The forest is not merely scenery; it is infrastructure.

Reforestation now faces an additional complication: shifting temperate zones. Species planted today may not be climatically suited to conditions decades from now. Adaptive management must account for projected warming trajectories rather than historical baselines.

Ozone and the Biofuel Paradox

Tropospheric (ground-level) ozone, formed through chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), is a growing stressor for forests.

Increased ethanol blending in gasoline — intended to reduce certain emissions — can unintentionally increase ozone formation under specific atmospheric conditions.

A study published in Nature Geoscience (September 2024) found that elevated ground-level ozone significantly reduces plant productivity in tropical forests. Researchers estimate human-derived ozone has reduced tropical net primary productivity by up to 10.9% in parts of Asia, contributing to a loss of approximately 0.29 petagrams of carbon per year — roughly 17% of the tropical land carbon sink since 2000.

Ozone harms human lungs — and it harms forests. The atmospheric chemistry of modern energy systems carries ecological consequences that extend far beyond tailpipes.

Climate Change and U.S. Temperate Zones

- Rising Temperatures: Warmer averages and more frequent heat extremes alter growing seasons and stress ecosystems.

- Precipitation Volatility: More intense rainfall events increase flooding and erosion, while longer dry periods strain water systems.

- Ecological Redistribution: Species ranges shift northward and upslope, creating mismatches in pollination, migration, and food webs.

- Agricultural Stress: Heat, drought, and extreme weather affect yields, pest dynamics, and economic stability.

- Wildfire Risk: Warmer and drier conditions increase fuel availability and fire frequency.

- Public Health Impacts: Heat stress, air pollution, and vector-borne diseases disproportionately affect vulnerable populations.

Trees, unlike many species, cannot migrate quickly. They remain rooted in shifting temperate zones, exposed to accelerating climatic change.

Conclusion

Climate change is not only warming the atmosphere — it is reorganizing ecological systems. Forests that once defined Pennsylvania’s identity now face compound pressures from heat, ozone, hydrological shifts, and biological competition.

The decline of Penn’s Sylvania is not merely symbolic. It represents a measurable transformation of temperate-zone stability.